The Dominos That Never Fell

Nearly a year after the collapse of SVB what have we learnt about the state of the global banking system

On March 10th, 2023, investors awoke with a shock. A highly rated bank in California had gone bust in what was the second biggest bank failure since the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Two days later, Signature Bank, a smaller bank with assets of $110 billion, also fell. As the panic set in, investors fretted about the quality of Credit Suisse, and by March 19th, an institution with a history stretching back over 166 years was forced into a shotgun marriage with Swiss rivals UBS.

After 10 days of turbulence, senior investors worried that these collapses had all the hallmarks of the start of the 2008 Financial Crisis. The loss in confidence caused by the failure of a small bank leads to a domino effect which knocks over another bank and then another. However, the next domino never fell. Investors managed to calm themselves, and the banking system settled back down. Now that there is a little distance between us and this (relatively small) banking crisis, it might make some sense to take stock of some of the lessons investors have learned from this and what it might mean for how we think about risk in the banking system.

Lesson #1: Banking has changed

Banking is a unique industry. It’s the only business activity on the planet where a firm hopes its competitors are being well-run! Following the 2008 Financial Crisis and subsequent Eurozone Crisis, it became very apparent that too many banks had been poorly managed for far too long. The banking system looked so frail that a sudden stiff breeze would have knocked them over.

In the aftermath of these crises, there was a concerted effort by regulators, politicians, policymakers, and bankers themselves to improve the quality of the system. More stringent disclosure rules, scenario stress testing, and a demand for higher capital requirements were all part of the changes that have been introduced over the last 15 years.

The improvement in quality is reflected in the chart below, showing the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio for European banks. CET1 ratios are a measure of a bank's financial strength. It compares the bank's high-quality capital (like common stock and earnings) to its risk-adjusted assets. This ratio helps regulators ensure that banks have enough buffer to handle potential losses and remain stable. A higher CET1 ratio indicates a healthier and more resilient bank.

For European banks, there has been a marked improvement with CET1 ratios effectively doubling since the depths of the Financial Crisis. The increase in balance sheet robustness likely explains why further dominos did not fall in 2023, highlighting that the banking system is in much ruder health than it was only a decade ago.

Lesson #2: Dominoes don’t always line up

While the banking system is looking healthier, there were clearly weak points that were exposed with the collapse of SVB, Signature Bank, and Credit Suisse as contagion crept in. The concept of contagion implies that as one domino falls, it has a knock-on effect on a nearby domino. However, in March 2023, investors were reminded of the inherent randomness of banking contagion. Indeed, there were no tangible financial links between SVB and Credit Suisse, yet the two banks fell within 10 days of one another, almost like two seemingly unconnected dominos falling together.

The chaos of contagion was also witnessed in the fact that many issues about Credit Suisse were well known prior to its collapse, and a recovery plan had been well communicated. Credit Suisse had a tough decade. Following the crisis, many European banks, including Credit Suisse’s Swiss rival, UBS, sought to fundamentally change their financial structure. Risky investment banking operations were jettisoned in favor of less lucrative but more stable financial activities such as asset management and private bank services.

Credit Suisse opted for a different path. As its peers abandoned investment banking, executives decided to double down on investment banking, wagering that the lucrative revenues that had been present prior to the Financial Crisis would return. Unfortunately for CS, this bet didn’t pay off, and instead of profit, the company became mired in scandal after scandal. From suspect lending in Mozambique’s Tuna bonds corruption scandal to imprudent investment in the collapsed supply chain company, Greensill in 2021, as well as a $5.5 billion loss after Archegos Capital Management fell into trouble, highlighted a bank that seemed to be struggling with effective risk-management controls.

However, at the time of its collapse, all of the above was well documented by investors. Indeed, only in the last two years, the bank had been on a determined campaign to clean up the balance sheet and to move the institution onto more stable footing. The cleanup campaign had also been implicitly endorsed by the Saudi National Bank, which purchased a 9.9% stake in Credit Suisse as part of a large capital raise. Yes, CS had its faults, but they were well-known risks by March 2023. It therefore came as a surprise to some investors as to quite how quickly the contagion from SVB overwhelmed a seemingly unconnected bank. The whole crisis is a stark reminder of the randomness and confusion that can be caused when investors’ confidence dissipates and how suddenly almost anyone can find themselves in the firing line.

Lesson #3: Not all banking bonds are created equal

As the Credit Suisse domino began to topple, a niche area of the fixed-income markets suddenly came into focus, and investors began to learn more about banking bonds. Since the Financial Crisis, there had been a number of product evolutions and experiments designed to try to enhance the quality of bank balance sheets. One of these new products was Additional Tier One (AT1) debt, also referred to as “contingent convertibles" or “CoCos”.

AT1 debt first came into existence after the crisis in 2008 and are debt instruments exclusively issued by financial institutions. AT1 debt typically trades with juicy yields. At the time of writing, European AT1 debt trades with a yield in excess of 10-11%, far above the yield witnessed in European government bond markets.

However, with higher reward comes higher risk. Embedded within AT1 debt instruments is a conversion contract whereby if the bank starts to fail, the bond will ‘convert’ from a debt instrument into the equity of the bank. This puts investors in a tricky position. If the bank remains solid, they will receive a relatively attractive yield. However, if the bank fails, they will suddenly own bank shares that could soon be completely worthless. Regulators like AT1 debt because it theoretically acts like a shock absorber if a bank's capital level falls below a certain level and can be part of the capital cushion that regulators require banks to hold to ensure they remain robust during a crisis.

AT1 debt is a relatively new asset class, and fortunately, there have been only a few instances where investors have witnessed this ‘conversion’ process in action. Many of the European banks that have triggered an AT1 conversion were much smaller financial institutions (e.g., Greek bank Piraeus in 2020). The collapse of Credit Suisse gave AT1 investors a chance to see what happens in the event that a large banking entity begins to collapse; however, the outcome was very much unexpected.

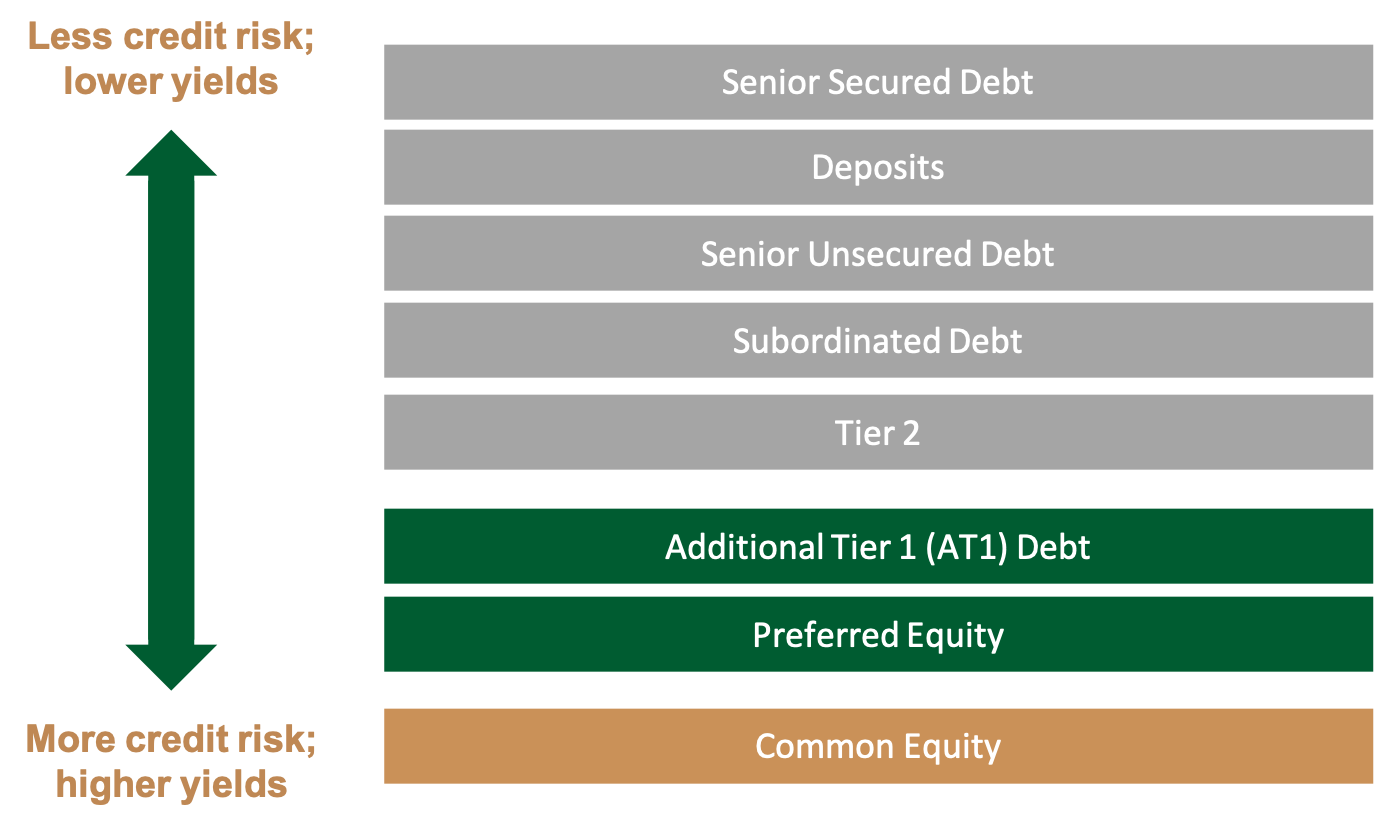

Theoretically, up until conversion, AT1 bondholders are higher up the capital structure than equity investors (see the diagram below). This should mean that they receive preferential treatment in the event of a liquidation ahead of any shareholders.

However, the terms of Swiss AT1 bond agreements state that in the event of a restructuring, the rules of the traditional capital structure do not need to be respected. When Credit Suisse collapsed, almost overnight, the Swiss financial authorities repositioned the company’s capital structure. AT1 bondholders were almost entirely wiped out; meanwhile, equity shareholders in the banks received compensation amounting to 82 cents per share.

Why did Swiss regulators effectively demote AT1 bond holders so drastically changes remains an open question. There were rumblings of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund having equity exposure and that they were unhappy with the initial deal which prompted changes.

Investors were sent reeling by the decision. Questions were being asked as to where exactly AT1s sat within the capital structure? Were bondholders no longer senior to equity investors? And if not, then did this not constitute additional risk that justifies higher yields as more compensation for this risk?

While the Swiss financial regulator messed around, British and European financial regulators quickly stepped in to clarify that while the Swiss technically had the right and ability to change the rules, had Credit Suisse been domiciled in another European country, the treatment of AT1 investors would likely have been quite different. In short, investors effectively discovered that while AT1 bonds may all be called the same thing, in reality, not all of these subordinated banking bonds were born equal, and some behaved very differently from others, particularly in extreme situations.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog post is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, investment, or professional advice. The content is not intended as a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any securities or financial instruments. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. Always consult with a qualified financial advisor or professional before making any investment decisions. The author and the website assume no responsibility for any losses or damages that may result from the use of or reliance upon the information provided in this blog post.